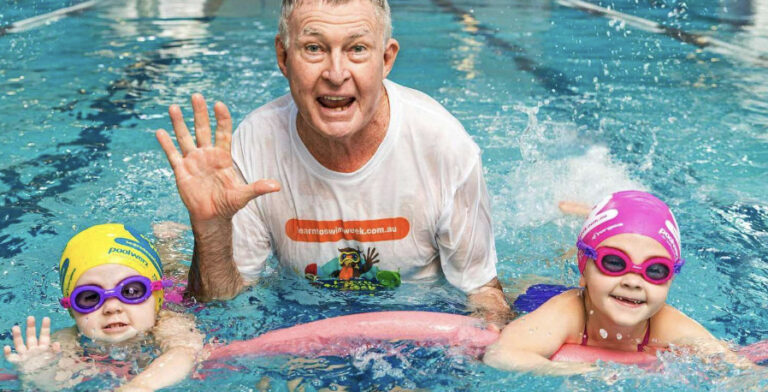

The Day Carlile Director John Coutts conquered one of swimming’s great challenges, Cook Strait.

COOK STRAIT is a formidable adversary even for shipping and not many swimmers would be prepared to challenge it.

It is the point at which the Pacific Ocean meets the Tasman Sea through the only gap in the New Zealand land-mass. Air streams approaching New Zealand converge and accelerate to pass through it. At its narrowest point – between Cape Terawhiti on the North Island to Perano Head on the South Island

– it is 14 nautical miles across.

The Strait has always been notorious

for treacherous currents, high winds and turbulent waters. Its tidal currents are completely erratic, depending upon conditions of wind and weather. In latitude

it lies in the wind belt known as the Roaring Forties and wind velocities of up to 240 kmph are recorded there.

After a southerly gale the turbulence is extensive, tides are strong and unpredictable and cold water from a depth of 1500 feet

is churned to the surface, causing the temperature of the sea to drop with dramatic suddenness.

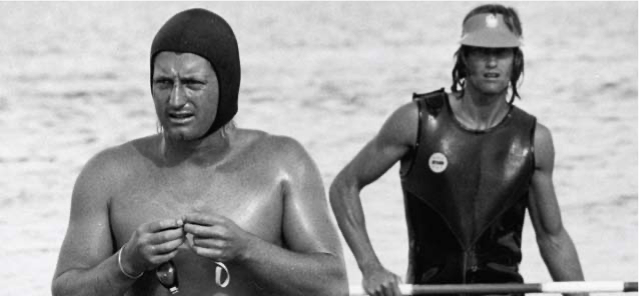

On 13 February, 1977, 20-year-old John Coutts, of Napier, swam from the North Island to the South Island in 9 hours 24 minutes, setting a new record for the Cook Strait

swim. In doing so, he became aware that he had experienced something touching far more deeply into the human spirit than the demands of sport or competition.

Climbers who pit themselves against the mountains say that, although they go to the high country to learn about mountains, they experience a new awareness of themselves and one another, and discover the power

of undemanding dependence upon each other. John Coutts and his support team experienced something similar in their team attack upon Cook Strait.

Fishermen who have worked the Strait for a lifetime have a healthy regard for its violence and unpredictability. Many travellers on the inter-island ferries would be prepared from bitter experience to endorse this.

History tells of at least one Maori, Whakarua- tapu, who, in the early 1800s, swam Cook Strait unprepared and unescorted by any escort boat.

He was in flight from Te Rauparaha and that fact was probably a better incentive than any record attempt.

The record for the Cook Strait swim was set by Keith Hancox, also of Napier, in February 1964, with a time of 9 hours 34 minutes.

John Coutts had been thinking of Cook Strait for some years but only as a daydream, the sort of adventure one likes to dwell upon, but never really expects to attempt.

He had been trained since the age of seven by well-known coach, Bert Cotterill of Napier and had clocked up an impressive record. He became New Zealand National Champion in three sports, competitive swimming, surf life saving and marathon swimming and broke over 100 New Zealand records. John won the 100m Butterfly at the Australian Open Championships in 1973 and a bronze medal in the 1974 Commonwealth Games. He became regarded by many as New Zealand’s top swimmer.

Coutts was familiar enough with the competition situation of pitting oneself against other swimmers. He knew what it

was like to put every ounce of effort into a race and feel and hear the support of the crowd lifting him through the water. He also knew that to set himself against Cook Strait would be a very different matter and that the crossing had been made in the past by swimmers of great strength and endurance with the courage for a lonely challenge, rather than by speed swimmers.

But a day came when he was able to ask himself – why not? Cook Strait is always there, always ready for a challenge. He knew himself to be ready. And the man who could organise and manage an attempt was ready – Ivan Wilson.

In 1963, Ivan Wilson had been trainer and organiser for John van Leeuwen, the only person to swim Foveaux Strait. In that record-making swim, van Leeuwen was in the water for 14 hours and had to swim 26 miles to set up his record. For six hours

of that time he was swimming through bluebottles and being stung all over his body. He was rescued from this by a fishing boat with whitebait nets that came by and trailed its nets between the boats, making

it possible to scoop up the bluebottles and allowing the swimmer to keep going towards his goal.

Ivan Wilson was the President of the Ocean Beach-Kiwi Surf Lifesaving Club. Both he

and Coutts knew that a good support team was essential. Wilson knew that it would be possible to find an excellent support team from Coutt’s fellow members, as six were already New Zealand Champions in swimming or surf lifesaving.

The next need was money. Wilson recalled that on the Foveaux Strait swim he had fed

van Leeuwen with Complan from a bottle. Other long-distance swimmers have eaten bananas and other favourite foods and have suffered from indigestion. Wilson believed

that the Complan meals had been a major contributing factor in the success of the swim. He intended to feed Coutts with the same mixture of Complan and glucose and he hoped for equally good results. He approached Glaxo laboratories, makers of Complan, and asked for their sponsorship. They agreed.

So, the finance was secured as well as the support team. Acting on the army belief

that time spent in reconnaissance is seldom wasted, Wilson surveyed the situation. Previous swimmers had been based at Island Bay, home of so many of the Strait fishermen. Being based there, however, meant a journey of two hours in a boat to the southerly point of the North Island. Travelling so close to the engine while in a state of nervous tension

was enough to make a swimmer sick before he started. It was decided that a base closer to Cape Terawhiti and Ohau Point, first and second choice in starting points, would be desirable. Richard Caldwell offered the loan of a cottage at Makara beach. It was ideal.

The team, the finance, the base secured. Now the experts.

The pilot: Paremata fisherman Reg McNamaway skippering the fishing boat Monowai; a man well acquainted with the changing moods of Cook Strait.

The navigators: Richard Davis and Brian Baggott, navigators on the inter-island ferries.

Two unofficial members of the team: Peter Gaston and Derry McLachlan, reporter and photographer sent by Napier newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, to cover the event.

They slept in the boathouse attached to the cottage and made themselves available for any task asked of them. They were known collectively as the D. T.s and by the end of the affair were so much a part of the team that their attitude was anything but coolly professional. While they got stories and good pictures for their paper, they also gave great moral support.

On the fishing boat, Mazurka, skippered by Dennis Palmer, travelled the TV1 crew, Radio New Zealand reporters and Wellington Evening Post reporters.

Keith Hancox, holder of the Cook Strait swim record reported for Radio Windy and zipped rapidly in and out in a jet boat. The support boat carried his petrol supplies.

The team; the finance; the base; the Cook Strait professionals. Lastly, the equipment.

Coutts had spent much time in the sea learning the hard way. He knew that properly

fitting goggles were an essential if his eyes were not to swell up.

He had learned in his trial swim in Hawkes Bay from Tangoio to Napier that, unless his chin was closely shaven, it would rasp against his shoulder when he threw his arm over and, in a long swim, it would take off the skin. A razor for last minute use was part of the equipment.

Then the contentious matter of the head- covering. Other Cook Strait swimmers had swum without caps, but Ivan Wilson was convinced of the wisdom of wearing a cap, as protection from the cold water for the ears and the nerve centre in the top of the head. He believed that covering for the head and ears was as necessary as goggles to protect the eyes.

Keith Hancox, Strait record-holder for

13 years, told Wilson before the swim that he believed Coutts’ bathing cap would be considered an inadmissible aid in swimming and thus contravene the rules laid down for English Channel swims. Wilson replied that he considered the cap a hindrance rather than an aid to swimming but a medical necessity without which he would not allow a long-distance swimmer to remain hours in cold water.

He pointed out that van Leeuwen had worn an identical cap in setting the Foveaux Strait record and had gone unchallenged, that there was no governing body to lay down rules for record swims in New Zealand and that it was high time that there was such a body.

The team left Napier on Monday 7 February at 6.30am. John Coutts was suddenly overawed by the fact that what had been his own private dream had become a hard reality, involving not only his friends,

but many strangers of professional ability, newspaper reporters, television crews, boats and helicopters. And all of them moving purposefully upon Wellington, just because he had entertained the thought that he would like to swim Cook Strait and thought he could do it in less time than Keith Hancox.

They lined up to have the first photograph taken outside the Wilson house, the first

of many excellent photographs by Derry McLachlan. Much aware of their responsibility

to their sponsors they all wore the White Horse jackets donated by T. & G. McCarthys. There was Coutts the contender and Ivan Wilson with his daughter, Anne Bauer, who was joining the party as cook.

As a social worker, Wilson had plenty of experience working with young people who had become defeated by society and their own circumstances. This team of surf life- savers were young people who were receptive to training and discipline, self-disciplined and keen to render a service to the community.

To weld such a group into a solid unit, and bring his own administrative skill into play to help one young sportsman test his courage and endurance against the unpredictable, disastrous Cook Strait was a challenge Wilson could not resist.

Leading the Ocean Beach lifesavers was Brian Wilson, aged 28, son of the team manager, champion ski-paddler and swimmer. As the oldest member of the team, he was generally regarded as the anchor stone, a tower of strength and purpose, and as the week went on this dependence upon him grew.

He was the only one with experience of Cook Strait, having made an attempt on the record himself, when he was only 16. Privately Brian wondered if John Coutts had any idea of the enemy he was pitting himself against, but he kept his thoughts to himself and offered only encouragement and confidence.

The rest of the team were Bruce Clark, aged 25, ski-paddler; Daryll Gledhill, aged 20, ski-paddler and swimmer; Pat Benson, aged 20, swimmer; and Peter Brough, aged 16, ski-paddler and swimmer. Peter was known as Frank because he was accident- prone, yet always good for a laugh. Benson was the only one who had not been in training for the swim as university studies had prevented him.

The convoy set out from Napier with Bruce Clark driving the Bedford van newly bought by the surf club to get members of the

club from their homes to their duties at the beaches. Most of the team and most of the gear was in the van. Next came the two D.T.s in their van with Ivan Wilson and Anne Bauer bringing up the rear.

They arrived at Makara via the tortuous back road from Johnsonville at 1.30pm. They drove up to the cottage feeling ready for any challenge land or sea could offer, but they had not reckoned on television.

The TV1 crew was waiting for them and they went straight into an ordeal, compared to which swimming the Strait seemed mere child’s play. After trying to obey instructions to stroll naturally and chat casually as though there were no lights, no television crew, no reflector boards and no camera, they could only console themselves that at least they were better swimmers than actors. Coutts and Wilson had to go through personal interviews, not once but several times.

The team settled into the cottage and were joined by Gary Finderup, publicity manager for Glaxo and thereafter known as Gary Complan. The D.T.s took up residence and set up their press office in the boatshed. The TV crew came and went.

Ivan Wilson found accommodation with Jean and Reaston Bailey, Makara storekeepers. He knew he would be ringing the Weather Office at three-hourly intervals during the night and he wanted to ensure that everyone else had an undisturbed night’s sleep.

The plan of campaign had been for the team to be at Ohau Point at 3pm on the

day of arrival for a first swim catching a tide similar to that they could expect on Thursday morning, the day picked for the attempt. This was the first disappointment; a strong northerly wind and a choppy sea caused a change of plan and the swimmers went off to Lyall Bay and quieter waters. In Coutts’ first encounter with his adversary, the Strait had showed its contrary moods.

Richard Davis, navigator, Reg McNamaway, pilot and skipper and Ivan Wilson, manager, studied the charts and discussed plans and possibilities. Then everyone went to bed and slept soundly except the manager who began his three-hourly liaison with the Weather Office, saying goodbye to real sleep until the attempt was over.

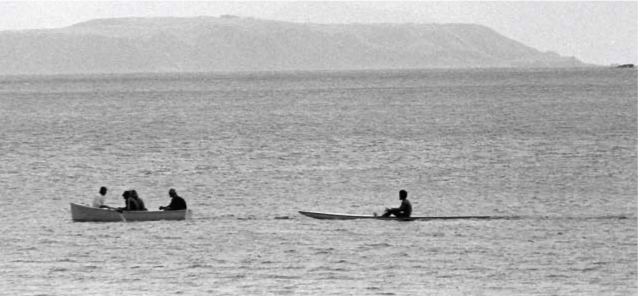

Tuesday 8 February: The trial swim was on – a relay across to the South Island to give everyone a chance to test out the tides, the

temperatures and the moods of the Strait.

All were in high spirits with high hopes. The organization was ticking over like clockwork. The newspaper and TV people were at the ready, the support team on their toes and the contender was calm and confident.

It had been decided to start across the Strait from Cape Terawhiti, the point of the North Island closest to the South Island. Everyone had heard about the notorious Terawhiti rip but it was decided it could be tackled. John Coutts started off and swam for two hours with Bruce Clark beside him on a ski. Cook Strait played its first ace.

As Ivan Wilson said: “The Terawhiti rip is the most disastrous bit of sea I have ever seen. There is a great turbulence in the water and vicious tides. The tides are like arms coming out to grab you. It is like being in a washing machine and unable to get out”.

From the escort boat it looked as though both swimmer and ski-paddler were being sucked into the rip. The ski-paddler was directed by loudhailer to move Coutts out of it and the team on the boat watched in suspense as the two in the water struggled for half an hour to pull themselves clear of the clutching water. Even as they reached the edge of the rip the watchers had the weird feeling that it was still reaching out at them, trying to draw them back and engulf them.

Bruce Clark explained how it was: “We did not go all the way into the rip but we went as far as I’d ever want to go. It was a bad bit of sea. My main concern was that I wasn’t doing my job properly as far as John was concerned. I was there to help him but it took all my effort to look after myself, stay on the ski and not

be washed off by the heavy swells. In normal surf you can see the high seas coming but in the rip they come at you from every direction. You position yourself for one and another comes and gets you from the side or from behind. I was supposed to be paddling quietly along beside John, but I was frantically back- paddling all the time trying not to hit him”.

On board the escort boat Ivan Wilson got ready neoprene rescue tubes to haul both swimmer and ski-paddler out of the water

if it became necessary, but Coutts swam on

through the turbulent water and kept up a steady 75 strokes per minute, in spite of seas breaking over his head on occasions.

Once out of the rip, things were better. After two hours Coutts left the water and Brian Wilson swam for 75 minutes before getting cramp. Peter Brough then got in

and swam on. They were halfway across the Strait in three hours and everyone was very happy about timing. Then the southerly wind increased from 15 to 25 knots and the seas grew bigger and bigger and finally the relay was abandoned. There seemed little point in allowing the swimmers to beat themselves into exhaustion when the big test still lay ahead. The relay had been a test swim only. Everyone had limbered up and had the chance to test out the Strait. Spirits were high and hopeful. With this speed and form they all felt that Coutts could easily clip two hours off the record.

Ivan Wilson knew that if Coutts could swim like that in those conditions and still be half an hour ahead of schedule, nothing could stop him on a fine day.

On meeting the Strait, John Coutts likened the experience to “hopping into a cage with a tiger, but then finding out that the tiger was not as vicious as everyone said”. He could now think of the Strait, not as the mythical enemy, but as just another stretch of water. “We could cope with it. We could defeat it”.

The manager, the navigator and the pilot sat down to look at the charts again in the light of what the day had taught them. One thing was agreed upon. Coutts would not now start from Cape Terawhiti and head again into the rip. He would start from Ohau Point. This would make the swim half a mile longer but it had the advantage of skirting the rip.

Wednesday 9 February: the day it should have happened. This was the day the Weather Office picked and this was the one day when John Coutts could have made the double crossing. The winds were right, the weather seemed settled. The sea was warm and the forecast was for fine and mild conditions. The forecasters were delighted that they had been able to do the right thing by the team and produce the right sort of day. Cook Strait was

beautiful and calm and there for the taking. The tiger was behaving like a lamb.

But the television crew had been working on Thursday as D Day, not Wednesday. And the Glaxo people had publicity plans in hand for Wednesday. Furthermore, the fishermen were not eager to go because it was still the time of the spring tides. It was cold and frosty before the dawn. While it was still dark, Ivan Wilson spoke to the milkman who commented that this was the first frost of the year. Coutts would have had to start out at 5.30am in the darkness and the cold. He might not have been able to get properly warmed up again in spite of the fact that a still, calm day could be expected after the early morning frost. Also, Coutts had mentally prepared himself for Thursday.

Wednesday, the perfect day, came too soon. No one was ready for it and it brought a frost with it. No one was ready for that, either. And so the attempt was not made on Wednesday.

Thursday 10 February: the tiger showed

its teeth. Cook Strait had presented its kind and mild face for just a day and now it blew a howling southerly wind to whip up the sea.

Friday 11 February: the wind went about and a southerly gale came in from the opposite direction, churning the sea into greater turbulence. The team had to miss out on the sea altogether and go to the Freyberg Pool to practice. Spirits became pretty thin.

Saturday 12 February: the weather was better but it was still too windy and choppy to contemplate the attempt.

Time was running out. Most of the team were due back at their work on Monday. The days of suitable tides would soon pass. These days of disappointment were later seen to have been of value. Peter Gaston viewed those extra days as “probably necessary to weld the group into a unit that would not collapse when the strain came at the end.

“They gave Coutts time to learn the strength of his team, to know their individual strength and how to draw upon it”.

For Derry McLachlan that week of being together, facing disappointment cheerfully, supporting one another against growing frustration was “the way championship teams are made”.

There are not too many lonely champions. A champion usually achieves what he does on the strength of his support as well as on his own efforts. It takes strength of character to reach champion status and character is not formed by an effortless ride to the top. It is formed out of self-discipline imposed by disappointment

Thursday, Friday and Saturday could

be regarded as part of the training. They were days of high winds, poor seas and diminishing hopes and during them every member of the team worked to keep spirits high, by any childish game or skylarking they could think of.

Brian Wilson proved his leadership during this time by initiating all kinds of hilarious contests. There were eating contests, burping contests, draws of the cards to decide who would sit where and for how long, who would wear which hat and at what time everyone would be obliged to change hats.

A visit was paid to the Weather Office to meet the forecasters on whom the team was to rely so heavily. Children from Makara School came down to the beach to watch

the television crew at work and Coutts spoke to them and explained the plans for the attempts. A visit was paid to 88-year-old Joe Volpicelli, a fisherman who had worked Cook Strait for 70 years. He spoke with knowledge and authority of tides and rips and sharks. His advice on sharks was – “as long as they leave you alone, you leave them alone.”

When, despite all this, spirits were flagging, Mrs Bailey brought the team

the biggest and best pavlova they had ever seen. She also rang the radio station and asked them to put over a call and a word of encouragement to the team. Her thoughtfulness and concern as much as her cake raised their spirits again.

Mrs Bailey ran a Bible class for Maraka children. She had the children praying for Coutts’ success and who could ever measure the effectiveness of their prayer? She kept telling Coutts to have faith.

“If the Lord doesn’t want you to go today you won’t go today. But he will give you a good day. Just have faith.”

Then came Sunday 13 February, and for many of the team it was their last possible day. Sunday the 13th started like every other with a 3am call to the forecasters. This time they didn’t say – “You should have gone on Wednesday. We gave you a good day then.” This time they said – “Today might be the day.” The forecast was reasonably good. A 15 knot wind was decreasing and the seas were not heavy.

At 3.15am Ivan Wilson rang Reg McNamaway and the two agreed that the

day, the tides and the winds seemed to be coming together satisfactorily. Ray telephoned Dennis Palmer, skipper of the Mazurka, TV1’s boat. Wilson rang Max Pudney, supervising technician with the TV crew. The message to both was the same – “We’re going today.”

At 5am Wilson went over to the cottage and woke up the boys and told them the same thing – “today’s the day”.

Everyone went into action. Someone cut the sandwiches, someone filled the thermos. Brian, the chemist, had mixed the bottles of Complan the night before just in case.

Ivan Wilson packed the bag. It was a cricket bag, specially bought for the purpose and marked MCC to emphasise that it was no ordinary cricket bag. Item by item the check list was ticked off and the MCC bag was filled. Into it went: surf line; 4 thermometers (all of which got broken; 2 transistor radios;

2 shark spears; 1 rifle with 6 rounds of .303 ammunition; 4 bluebottle nets (remembering John van Leeuwen’s ordeal); 6 containers

of Complan; 1 packet of glucose; 1 jar of Vaseline; 2 jars of grease; 6 pairs of goggles; 3 bathing caps; 2 charts of Cook Strait; binoculars; 1 tin of sea rescue paint (orange, to mark landing place); 1 bottle of White Horse Whisky and 6 White Horse jackets (from T. & G. McCarthy’s, Napier); 1 loud- hailer; containers for Complan and funnel; 4 spare swimsuits; cotton wool; 6 containers of seasick pills; 12 towels; 4 wet-suits; and spare batteries for the loud-hailer.

Seasick pills were issued to all the team except Daryll Gledhill, who unfortunately missed out. He was to suffer for this omission through the day but it did not stop him from

carrying out his part in the support team. John Coutts did not take a pill.

Then everything was loaded into the van and the party was on the beach at Makara at 6am. It was dark, calm and peaceful pre-dawn with the stars still shining. They collected Reaston Bailey’s rowing boat and took it down to the beach to await the arrival of the escort boat.

For John Coutts it was “unnerving really”. For so long it had just been an adventure they had talked about and made long-distance plans for, now it was for real. It was happening.

At 6.15am Reg McNamaway came speeding round the bluff in the Monowai to pick them up. Reaston Bailey ferried everyone out to

the fishing boat and his good wishes and encouragement followed them as the skipper turned the boat towards Ohau Point. John Coutts looked over towards the South Island in the dawn light… and he wondered.

Brian Wilson rubbed Coutts down with Transvasin and Ivan Wilson rubbed him down with grease. They had hardly finished when the boat arrived at the starting point. The other escort boat with the dinghy had not

yet arrived but Keith Hancox in his jet boat had. Hancox, who was doing a commentary for Radio Windy, came alongside and offered to take Coutts to the shore. The offer was gratefully accepted. There seemed something fitting in the holder of the Cook Strait record helping to start off the young contender for the same record. When Coutts was in the jet-boat ready to go and Ivan Wilson was delivering his final advice and instruction, the matter of the bathing cap was re-opened.

Hancox asked Wilson whether he had reconsidered the use of the cap because of

its implications? Wilson replied that he had reconsidered it and was adamant that Coutts would wear it. “We in New Zealand are not tied by any rules for this swim. We’re all Kiwis and overseas rules do not bind us here,” he said.

Hancox then took Coutts to the shore with his first pacer, Daryll Gledhill. Little time was wasted in making a start.

Coutts had a small problem at the start. When he put on his goggles – a brand new pair – the elastic broke. With no time to waste,

he tied a knot in the elastic and put them on. The knot held for the whole journey. He afterwards gave the goggles to Mrs Bailey as a momento.

The sea’s temperature, tested with a bath thermometer, registered 58 degrees – “cold bath” marking on the scale. Wilson had planned to wait for 62 degrees before allowing the attempt to start.

John Coutts stood on the shore and looked over to the South Island thinking – “gee, that’s a long way. Oh, well, it’s now or never.” He threw up his arm as arranged to signal the start. Everyone checked their watches and confirmed the time – 7.20am.

“See you on the South Island then, “ Coutts said. He went into the water and started swimming towards the hazy land-mass in the far distance.

Two ski-paddlers waited about 20 yards out and took up station beside Coutts. Brian Wilson was on his ski two yards to the left of the swimmer and, with only a short break,

he was to remain there until the finish. Daryll Gledhill swam with Coutts and Bruce Clark was two yards outside him.

The escort boats followed about 20 yards behind. The basic instruction to Coutts was that he would not touch any object but the feeding bottle and all pacers were instructed to avoid any bodily contact with him. These instructions were obeyed to the letter.

7.50am: it was time for the first meal. Coutts was elated to be told that he had swum 1.5 miles in his first half-hour. His stroke rate was 78 per minute, higher than that of any previous aspirant to the record. He was breathing only on every fourth stroke, an indication of his tremendous lung capacity.

In the next half-hour period, Coutts touched the edge of the Terawhiti rip. The watchers on the boat were aware of the danger but it did not unduly trouble the swimmer. John Coutts commented that “it got very choppy and a lot of swells came up over my head. My arm was being forced back in mid-stroke.”

Ivan Wilson said that they could see the rip reaching out to grab Coutts. He shouted to the ski-paddlers to keep him out of it.

8.20am: at the second feed stop, the rip was left behind and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. A speed of 2.6 nautical miles per hour was being maintained. Prospects looked good and everyone on the escort boat was jubilant.

However, Coutts was less happy. The cold of the water was beginning to get to him, causing swelling in the groin and severe pains in his hips and legs. His powerful arms were doing all the work and his legs were trailing but he still maintained his fast rate.

Coutts was used to swimming in the normal 65 degrees of the sea in Hawkes Bay and the fact that he was unaccustomed to such cold water is probably the reason he was so severely affected by it.

As Brian Wilson expertly managed his own ski he put into practice what he had impressed upon the other support team members: Don’t look around to see what is going on. Concentrate on Coutts. Keep your face turned towards him so that every time he turns his head to breathe he will see you looking at him, projecting strength and confidence.

Smile at him – project your concern. If you look weary or bored you’ll communicate that to him.

Brian Wilson, the only one who had experience of being a Cook Strait contender, understood what Coutts must be feeling

as pain struck him and he came to the full realisation of the nature of the endurance test he had undertaken. He got into the water with Coutts at his meal break and talked to him and encouraged the swimmer to talk out his feeling.

Coutts had only one desire at this time. He wanted to turn onto his back and pull his legs up to his chest to relieve the pain in his hips. Brian Wilson warned him against it and, Ivan Wilson, from the boat with the loud-hailer, told him he must not because if he did he would certainly get a cramp in his legs.

Coutts swam on, existing from one meal break to the next. The ski-paddlers arranged a time signal. At the halfway point between two breaks – 15 minutes – they would turn their peaked caps back to front. When he saw this Coutts would know he was getting close to his

next relief. The pain in his hips began to get unbearable at about the 23 minute mark and the last seven minutes of every half-hour was a grim and determined effort to hang on.

At this stage Coutts began to see his support team in a strongly individual light so that at one time he felt the need of one of them beside him and at another time one of the others. Each gave his own form of support – Daryll Gledhill, full of courage in spite of feeling ill; Pat Benson, with a special strength and reliability of his own; and Peter Brough, the only one who could manage to make Coutts smile in bad moments.

For Coutts “my support team felt like part of me. They were me and I was them. Every time I turned my head I saw one of them there beside me and beyond him the guy on the ski. You reach a barrier of pain and from then on

it doesn’t let up. In warm water you should be able to swim for five to six hours before you hit that pain barrier but in this swim it hit me at one and a half hours. Those guys alongside me carried it with me. Things didn’t seem so bad when they just talked.”

Pat Benson described how he “talked to Coutts about Peter Snell and John Walker. Neither of them ever had to put as much into their victories as this poor guy was putting

in. Once he said “I’m not going to last much longer, Ben,” but he didn’t mean it and I knew he didn’t mean it. I told him he would make it and I would swim all the way to the South Island with him if he wanted me to. I tried to make him smile but Peter Brough was the one for that.”

When Brough got into the water and talked to Coutts, those watching were able to breathe a sigh of relief as they saw a grin emerging below the goggles. This brought smiles all round.

Coutts moved through the endurance of Gledhill, the warmth of Benson, the humour of Brough. And beyond them, to the skis, Clark and Wilson, keeping close station, handling their skis impeccably in the swells, with faces of determination and the will to achieve.

Everyone concerned with the swim had been much aware of the danger of sharks, although no one liked to talk of it very much.

On the escort boat a shark watch was kept at all times by a lookout with a rifle beside him. The two Daily Telegraph men had undertaken the lion’s share of the duty.

Peter Brough was paddling a ski beside Coutts as pacer at about 9.15am when he saw what looked like a double black fin in the water and he thought it was a shark. His first thought was for Coutts and the shock the swimmer would get if he looked up and saw the fin magnified in his goggles. As Brough wondered whether to warn him or not, the double fin separated and Brough saw that it was two dolphins swimming close together.

More dolphins came speeding around this interesting flotilla in their territory and everyone on the boats crowded to watch them. A happy feeling spread. It was born of the belief that where the dolphins are the sharks are not and also of the pleasure that everyone feels when they see dolphins.

Peter Gaston was on shark watch when he saw the dolphins come. “Some of them were riding our bow wave, enjoying themselves. Then they went across to the Mazurka and hitched rides on their bow wave.

Others played around the boats. Three of them in graduated sizes and looking like father, mother and baby, swam towards the boat in perfect formation, dived as they reached it and came up to the other side, still in formation. A group of them took up station in front of Coutts and for about 50 yards they paced him. Then it was just as

if they suddenly said: “You’re far too slow for us, mate, with your 2.5 knots an hour. Lift your speed up to 20 knots and then perhaps we could have a good time together.” Then they shot away to see what other interesting things the sea had to offer.”

Everyone felt happier and more relaxed for their coming, except Coutts. His pain never diminished and he hauled himself through the sea by the power of his arms. But he maintained his speed.

He began to wonder how long his support team could stand the cold water for he realised that they had to suffer it anew every time they got in to swim with him or bring his food.

But according to Peter Brough: “People get like machines in the end. John just swam

on and on. I sat on the boat and looked at the time about every minute. The others just sat on their skis. No one seemed to be going anywhere. John’s whole personality seemed to be changing. He looked sub-human, eyes distorted by the goggles, lips swollen, face puffed out.

“When it was time to take his feed bottle to him in the water it was so cold I’d be thinking – for heaven’s sake, drink it as fast as possible and let me get back on to the boat. And I’d get back and get warm again and then it would be time to get into a wet-suit and go in and swim with him – and there isn’t anything colder and wetter than a wet, wet-suit. But there was no let-up for John. He just had to keep on swimming.”

Coutts was by this time suffering acutely and he told himself that he did not have to endure all this.

The thoughts went round in Coutts’ head: “There’s an easy way out. You can just simply get out of the water. You think what it would be like to be up on the boat, wrapped in a blanket and going home. But you have to tell yourself no.

You have to learn to say no to yourself. It hurts too much. You’ve come too far. Everyone’s done too much to give up now.” So he swam on.

Ivan Wilson observed that during the most difficult part of the swim, when most swimmers would be tiring, Coutts swam his fastest. His stroke rate increased to over 80 strokes per minute and his pacers had to push themselves to keep up. His will to beat the record was fantastic.

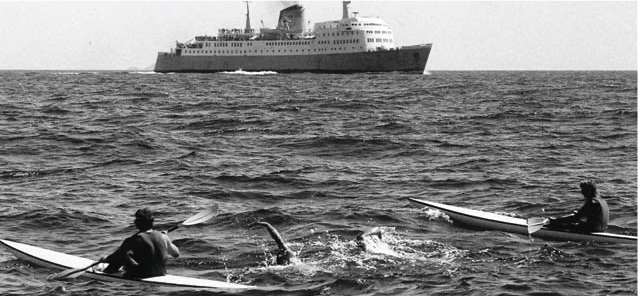

The passing of the inter-island ferries provided a great boost to everyone’s morale. They saluted the swimmer with loud blasts on their sirens and one of them swung off course and came within a few hundred yards of the flotilla. The passengers could be seen lining the rails and waving and urging him on.

John Coutts felt so glad to see them. “I wanted to stop and wave back to them. I didn’t but I did manage a slow arm stroke with a wave on the way.”

He could see the southbound ship for some time afterwards as it made for Tory

Channel. It got smaller and smaller on the horizon. The South Island seemed a long, long way away.

Peter Brough thought that it was terrific when the ferries greeted them in this way. “The sea was getting to feel pretty lonely and then suddenly there were all these people waving and shouting encouragement and their great big ship giving us a friendly blast. One of them came very close and we swam on through its wake for some time afterwards. It was a stretch of flat water like a footpath laid down in the sea and we swam down it.”

Like the dolphins, the ferries were a happy encounter in a picture growing more and more grim. At 10.30am, with seven miles still to swim, Coutts was keeping up a stroke rate of between 70 and 80 strokes per minute.

An hour later, as he was telling himself that he now had only five miles to go, he had to be told that it was still seven as he had drifted considerably. Psychologically it was a severe blow and it undermined his confidence. He no longer wanted to listen to words of advice and encouragement over the loudhailer. Ivan Wilson was prepared for this rejection but

it hurt.

Ivan Wilson remembered John van Leeuwen reaching this stage on the Foveaux Strait swim and telling him – “Nobody could be expected to endure what you expect me to endure.” Wilson nearly took him out of the water then and if he had he would have robbed him of the record. As he said: “I’m a social worker. My job is to help people avoid the point of killing strain. Today my job was to force this boy on to his limit and beyond it. But it was not easy for me.”

Wilson got Brian Wilson out of the water. He showed him the charts and explained to him what had happened. He sent him back to Coutts in the water to explain it to him and try to rebuild his confidence. He told him to tell Coutts that the slack tide would very shortly bring him some relief. Brian Wilson took Coutts his feed, talked to him and reassured him. Coutts responded and tried to put the disappointment out of his mind.

The water seemed a little warmer, the sea a little less choppy and his stroke rate was still excellent. A period of slack water would be

welcome, it would allow him to make better time and to increase his chance of reducing the record considerably. The team on the escort boat shouted encouragement. The TV helicopter passed overhead, heading south, waiting to film the finish. Coutts started off again with fresh heart. The South island did not seem so very far away.

But Cook Strait, the unpredictable, had another trick ready to play. The slack tide came and went in 30 minutes and the expected long period of slack water did not eventuate. Instead, Coutts went into an epic struggle against a northerly tidal rip against which progress was impossible.

On board the escort boat the elated mood evaporated and it stayed that way until the last moments of the swim, hours later. The planners were now talking gloomily about the course they should have plotted… if they had known… about three miles to the south so that this relentless tide could have carried Coutts on to the South Island instead of implacably trying to force him back to the North Island. They thought now that they should not have swum him so tight on the tide, they should have angled him more… had they known, had they only known. But who could know what the Strait was likely to do at any given time?

Coutts battled the strong northerly tide with all his strength while the time he had notched up against the record slipped away moment by moment. It was obvious that he was going to overshoot Perano Head, the planned landing place. Instead of the South Island looming up ever close, it was slipping sideways past him.

John Coutts was swimming as fast as the tide was coming towards him so he was a match for it and was able to keep level. A female swimmer might not have the physical strength to even keep level and so would actually lose ground.

It seems likely that this was the factor that forced the courageous Sandra Blewett to give up her attempt on the record on the same day.

Pat Benson, who had been in the water for four hours, got back on to the boat and had a severe attack of cramp in his legs. For a time

he watched Coutts battling the tide and then he turned and went below.

“ I couldn’t bear to watch,” he said. “It was the most moving thing I ever saw, this poor guy battling on and battling on and getting nowhere.”

Brian Wilson spoke of the frustration

of having to watch what was happening

yet be unable to help, of how sitting on a

ski seemed too easy in the face of such a struggle so that he felt an urge to get into the water and swim with Coutts and at least share the struggle with him.

Ivan Wilson had previously promised Coutts that he would be completely honest with him whatever happened. Now he broke that promise.

“John is a direct sort of person who needs the truth and I had promised to give it to him. But how could one tell him that in spite of swimming his heart out he was making no progress. It would have destroyed him.”

Peter Gaston described how “a gradual depression was coming over us all as we watched the record slip away, but at no time did anyone renege. They did whatever they were asked to do and they hid their feelings from Coutts.”

Suddenly, no one in the support team wanted to be told to take Coutts his next bottle of Complan. Everyone found it too hard to bear when he asked how far he had swum since his last feed and they had to try to be cheerful and evasive and not tell him that he had made no progress at all. “Don’t worry about what’s behind you. Think about what’s ahead. There’s the South Island. Go for it.”

Derry McLachlan said: “I’ve seen a

good few feats of endurance as a press photographer but I never saw one like those arms going over and over for all those hours. Our hearts were absolutely bleeding for him when he was making no progress. It was intolerable. Many of the people on the boats were seeing sheer naked endurance for the first time and it shook them.

Another meal stop – “How much further now?” Coutts asked.

“Two miles. Go for it.”

Another half-hour’s painful swimming

“How much further now?”

“Still two miles.”

Coutts at last realised what everyone else

had known. He was only marking time in the sea and getting nowhere.

Ivan Wilson told how “at one time we had the Awash Rocks lined up with the Brothers Island and instead of moving on we stayed in this position for an intolerable length of time, a visual indication of the lack of progress even though Coutts was swimming as hard as he could.”

Then Max Pudney of TV1 called out “Look, the Brothers, it’s moving away.” And it was. The two islands were sliding apart. The hold of the tide had been broken.

Coutts began to gain ground. The sea was settled. The water was calm. The South Island was visibly coming nearer.

Coutts kept looking up at the land ahead. He’d ask: “How far now?”

“Only a mile and a half.”

“How far now?”

“Only a mile.”

The other guys were full of encouragement.

Keith Hancox went zooming towards the shore in the jet-boat, getting smaller and smaller and it was obvious that there was still plenty of sea between the swimmer and the shore.

By this time, after so many psychological setbacks, Coutts was not sure if he could trust anyone’s opinion but Brian Wilson had been with him all the way, strong and reliable, and he trusted him. And now Wilson was telling him: “I can see the breakers. Listen. You can hear the breakers. It isn’t far. You’re nearly there.” So he forced himself on and his arms ploughed the sea, his mind a blank.

Coutts said: “ I couldn’t have given a damn then and there if a shark had come and taken a big bite out of me.”

He lifted his head and looked towards the land and tried to guess the distance. Then he put his head down and swam on. He lifted it and took another look. It seemed even further away.

But now time as well as the tide were running against Coutts. He had never doubted that he could reach the South Island

but now he, and everyone else, had to face the possibility that he might not get there within record time. Ivan Wilson was in frantic consultation with the pilot, the navigator

and the skipper on the Mazurka. Coutts was going to have to race for the South island to have any chance at all. He would now have to aim for one point on the South Island and be driven into it by his weary support team. The question was – which point?

Derry McLachlan told how “this was a moment of incredibly high drama. Coutts was doing his share, swimming like a champion. The decision to be made would either give him a fighting chance at the record or else snatch away any hope. Coutts had no say in it. He had to trust the people on the escort boat and try to carry out whatever plan they decided upon.”

But the people on the escort boat were finding it hard to come to a decision. There were two courses open to them, two places to head towards. Skipper Dennis Palmer on the Mazurka informed them that the two places were equidistant.

Ivan Wilson had his eye on a small beach away to the side. To reach it Coutts would be swimming with the tide instead of, as at present, swimming diagonally across it. The navigators pointed out that to reach it the swimmer would indeed go with the tide, but he would also risk being taken by the tide and swept past the beach and away around the point. Time was running out and such a happening would take away any hope of the record.

No one was eager to take the responsibility for this last decision. Ivan Wilson, Napier social worker, felt that he could not be expected to know the moods and caprices

of the South Island tidal current and that this was a job for the local experts. But the experts knew enough about the Strait to know that

no one could predict what it would do in any given situation.

It was clear that someone was going to have to take a gamble and accept full responsibility for the consequences. Meanwhile Coutts battled on and the tension among the other watchers grew intolerable. They knew that

Coutts had to trust the men on the boat. They only hoped they were not going to let him down after his fighting effort.

Time was ticking away. From the boat the TV helicopter could be seen sitting on a hilltop, the sun glinting on its glass canopy, its crew waiting to see where the finish would come, ready to film it.

Everyone was waiting to find out where the finish would come – and there was only 20 minutes left for the record.

Derry McLachlan, Daily Telegraph photographer, joined Ivan Wilson. He passed no comment. But he looked at Wilson and his look said – “you are the manager; the decision is up to you, no one else.”

Then the two of them looked towards the little beach Wilson had picked out. The sun was glinting on the wet rocks. It seemed like an omen, a sunlit invitation.

Indecision ended, Wilson made the choice… “We’ll go for that beach”. Over the loud-hailer he instructed the ski-paddlers to make a 45- degree turn and head Coutts with the tide. They obeyed the instruction without question.

Peter Gaston said: “Once the die was cast everything started to go right, after four hours of frustration and growing depression. We knew he was going to get to the shore but was he going to get there in time for the record?”

The suspense was agonising. Everyone on the boats was gripped by it, wanting to get into the water and help in some way. Ivan Wilson produced the last weapon in his armoury, Pat Benson.

Benson had been a last minute addition to the support team. He had not trained for the attempt as the others had and, initially, he had not had the pace. But when it came to the finish Benson swam his guts out for John Coutts.

“Benson had great strength of character but he also had a special quality, he was completely unselfish,” said Brian Wilson.

The whole team had given Coutts everything they had without regard to their own exhaustion and depression. Now Benson was hustled up on deck from the cabin, where he had been recovering from severe cramp, to contribute the very last ounce

of help the team could muster. Wilson’s instruction was brief: “Get into the water and drive him on to that beach. He can’t beat the record unless you drive him.”

Benson joined Coutts in the water and

did just that. Bruce Clark described how: “Once we turned I knew we were right but I became obsessed by time. We could see the helicopter glinting on the shore and we could see the waves washing right up on to that little beach. Once we turned we didn’t have to paddle any more, the waves gave swimmer and ski-paddlers a lift.”

Benson got half a body length ahead of Coutts, turned and shouted at him and then raced ahead of him.

Coutts increased his stroke rate to 89 strokes per minute but Benson threw his whole heart into his effort and kept ahead. Every two or three breaths he would turn and shout at Coutts who would put his head down and rip into the sea in pursuit.

Later Coutts described how “Pat would yell and take off and I’d chase him. It was as though we were racing and he was winning.”

Coutts increased his stroke again but Benson was still in front and still shouting. Suddenly, people all around were shouting too. Some of the Mana Cruise Club boats had come over

to see the finish and some of the South Island crayfishermen had come out to watch. All were swept up into the excitement of the last minute race against the clock. Everyone realised that

it was going to happen. TV cameramen tried to get ahead to get to the beach first. On the escort boat there was pandemonium and the loud-hailer was snatched from hand to hand as everyone tried to put his own extra bit of support into the effort in the water.

Peter Gaston described the last moments: “I saw Coutts win his bronze medal at the Commonwealth Games and that time I heard the call from the crowd urging him on.

“Now the sea was ringing with identical call from the people on the boats – go, John, go…

“And over it all we could hear Benson, still swimming for his life and still shouting encouragement and challenge. Then Coutts caught a couple of deep swells and he half butterflied up on to a large rock.”

Coutts’ goggles were a little fogged during that final sprint to where ever Pat was leading. He saw that they were in kelp but in the North Island that could be quite a way out from shore.

“Then, unexpectedly, there was the South Island in the shape of this large rock and we were on it, on the South Island. The finest thing I ever saw in my life was that rock.”

Pat Benson was concerned that Coutts should be seen to come right out of the water and up on to the beach so he urged him forward from the lovely rock. Coutts staggered up the beach, his legs giving way under him, after being out of use for more than nine hours. He threw up his arms in the prearranged signal and then the two of them collapsed on the beach and hugged one another. Tears ran down Benson’s cheeks.

“You made it,” he said.

“No,” said Coutts, “we’ve made it.” It was 4.44pm. Coutts had made the

crossing in 9 hours 24 minutes. He was the youngest man to swim the Strait. He had come ashore 3.4 kilometres north of his proposed landing place.

When the flotilla had made its dramatic turn with the tide, there had been only 17 minutes left to break the record. Coutts made the sprint to the shore in 7 minutes, breaking the record by 10 minutes.

Although Coutts did not manage to shave two hours off the record, as he had hoped, he could still be very proud of breaking a record that was hard-won against huge odds.

The two swimmers sat on the stony beach, Benson with his arm around Coutts. The TV helicopter hovered over them, creating a draught, making them shiver, blowing dust and stones around them.

The ski-paddlers joined them. Peter Brough silently handed Coutts a stone. He held it for a while, then asked.

“What’s this?”

“It’s your piece of the South Island. You’ve earned it.”

On the support boat, the organization, which had been impeccable, fell to pieces as soon as Coutts hit the shore. Everyone was emotionally drained. No one could think straight. No one could find anything.

Ivan Wilson started rowing ashore to pick up Coutts but his progress was slow and Coutts was getting cold so he called to Brian Wilson, borrowed his ski and paddled himself back to the boat.

There he was looked after by the skipper and the two Daily Telegraph men; all the team were either on the beach or en route to or from it. The Pressmen rubbed Coutts down and got him warmly wrapped in blankets. They asked him what he would like to eat and he told them that he had been thinking with longing for a tomato sandwich and a hot cup of coffee. It was then found that the thermos had been drained and all the sandwiches eaten during the hours of despondency,

so Peter Gaston got the makings of a ham sandwich from the television crew and Derry McLachlan got a thermos from Keith Hancox.

For Peter Gaston the most moving and dramatic moment of the whole affair was not the moment when Coutts hit the beach. It was the moment when Ivan Wilson got back to the boat from the beach and came face to face with Coutts below decks.

There was hardly a word spoken, just murmurings like “Well, we got there”, “Yes, we did”. But it was an intensely moving encounter. There was something between the two for that moment stronger than a feeling between father and son. They did not need

to speak. They could read it on one another’s faces. Everyone else could read it, too, and most were moved almost to tears. Fortunately, the camera can often capture what words cannot and Derry McLachlan caught the moment in a photograph.

Coutts tried to express his feeling, his realisation that it was a team effort and that he could not have taken the record without the team. And in the team he included the people on the boat and the two Daily Telegraph men who had caught the feeling on the occasion and poured their own hard work and support and spirit into the effort.

Coutts said: “It was for the boys. I didn’t think much about the eye of television on me. I just couldn’t give up because of the boys. They got me there. I don’t know how they did it, in and out of that cold water… Brian, 8 and

half hours on that ski beside me… and Pat…

I don’t know how Pat made that final sprint… I didn’t know he had it in him. And Ivan, behind it all… all of them, full of strength and support and heart.”

Peter Brough stayed behind on the beach and with the can of orange sea rescue paint, hopefully brought along for the purpose, he wrote on the cliff face:

RECORD. JOHN COUTTS. 13.2.1977

Then the boats all turned round and headed back to the North Island. The South Island slid into the sea behind them at a much faster rate than it had come up to meet them and soon they lost sight of the orange-painted message that told of an epic struggle that ended in victory.

The following year John Coutts swam from the south island to the north island in 6 hours and 46 minutes smashing the record by 2 hours and 38 minutes.

Story originally written by Kay Mooney Photographs by Derry McLachlan

(c) John Coutts 2006.